By Patrick Meaney & Ojas Chopra

Last year, AFSA shared a helpful blog post on unpacking the language of food sovereignty, looking at the key differences between agroecology and regenerative agriculture. In Australia, the term regenerative agriculture (or regen ag as it’s commonly referred to) is the language adopted by many farmers who are geared towards environmental stewardship on their land, such as no-tillage, soil cover, as well as crop and livestock rotation. We pointed out that the work of such farmers is to be commended, particularly in an Australian context where industrial agriculture still dominates our food system, producing far too much food for exports and squandering far too much of our land, water and soil in the process.

We put forward that Australian farmers should look to embrace agroecology as a science and social movement that incorporates the ecological farming principles found in regen ag, while having a strong political framework that enables grassroots momentum to challenge the dominant capitalist, industrial food system. What’s more, the term regen ag has already been co-opted by corporations as a greenwashing tactic.

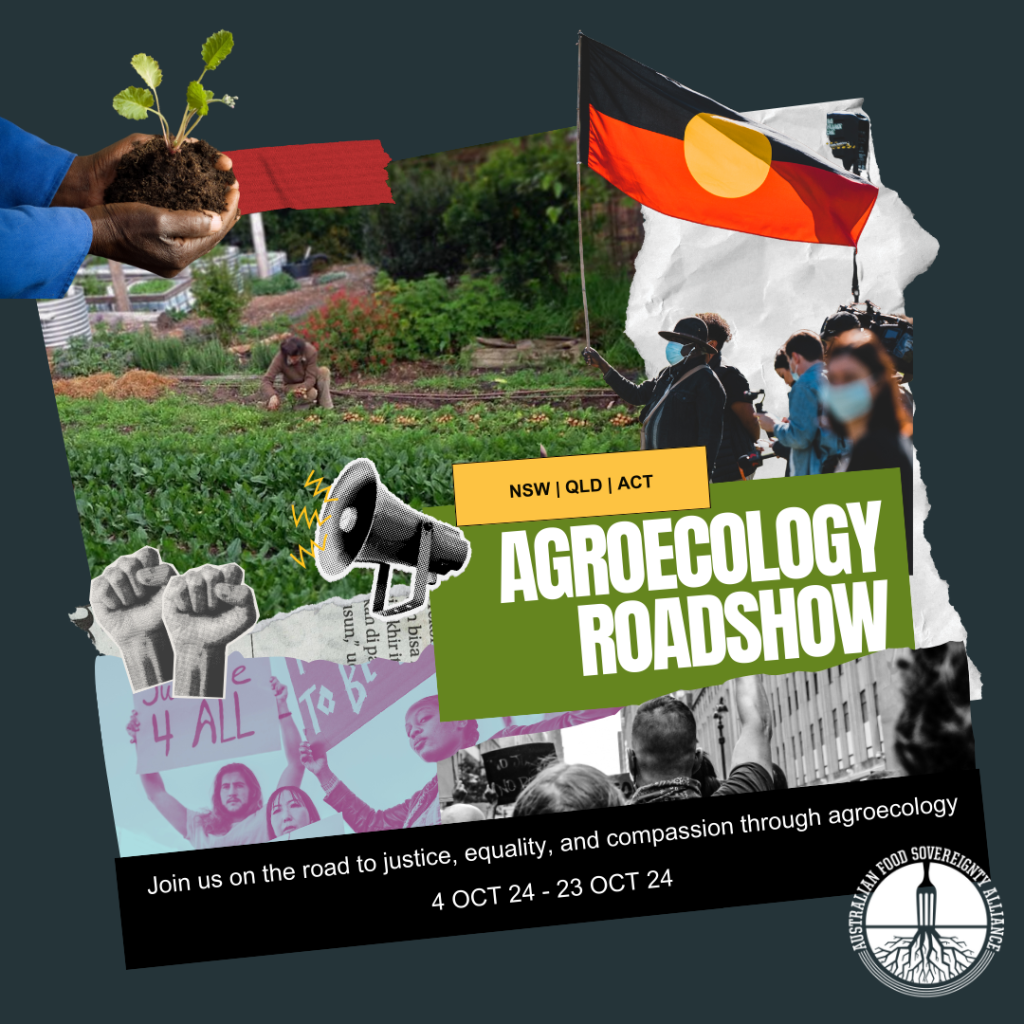

As we advocate for Australian farmers to think about the importance of language and adopt agroecology as the key mechanism to realise food sovereignty, does that mean that agroecology is not vulnerable to the same fate as the corporate co-optation as regen ag? Perhaps not. In this blog post, we look at how fake/junk agroecologies vs. real agroecologies are emerging internationally, and how we can avoid this in Australia during discussions at AFSA’s Agroecology Roadshow in October.

In recent years, the increased use of agroecology by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) presents a double-edged sword for our movement. On one hand, the promotion of agroecology rightfully acknowledges the role of peasant farmers, Indigenous Peoples and local communities who are responsible for feeding 70 per cent of the world’s population. On the other hand, as agroecology moves into mainstream policy settings, there is an inherent risk that corporations will latch onto this language obscure its political ties to food sovereignty as “the right of Peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

This has been seen predominantly within the regenerative agriculture movement, whereby the loosely defined practices of regen ag have been co-opted by conglomerates like Nestle, who hold claims to their own regen-ag model Regenerative agriculture | Nestlé Global (nestle.com).

In the international policy space, critique of fake/junk agroecologies vs. real agroecologies have emerged, and we believe it’s important to cast a light on what is meant by this.

What are fake/junk agroecologies?

Fake/junk agroecologies are symptomatic of the same greenwashing trend that has co-opted regen ag, whereby governments and organisations utilise the term to facade the ongoing “profit- and image-driven” (Giraldo & Rosset) practices of the capitalist colonial industrial agriculture system. Decision-making power remains in the hands of corporations and governments that do not honestly seek to catalyse systemic change within the food system. They are rolled out in a top-down fashion, with corporations or governments making decisions for, and imposing measures upon, landworkers, resulting in the loss of decision-making autonomy and ongoing dependency on the system. Within these fake agroecologies, the socio-political essence is obfuscated to benefit the bottom lines of those in power; “Serving to reproduce the dominant system and structures of power by stripping agroecology of its most autonomous, rebellious, and revolutionary facets”

What are ‘real’ agroecologies?

‘Real’ agroecologies – also labelled ‘emancipatory agroecologies’ by Giraldo & Rosset – as the name suggests, are true forms of agroecology which seek bottom up socio-political transformation focused on cultivating autonomy, and collective capacity within communities. Emancipatory agroecologies ultimately remove dependency on the violent industrial agricultural system and its markets, the very system to which agroecology stands in contrast.

Peasants, or smallholders, continue to be “tiny engines of abundance” generating wellbeing for themselves and the ecosystems in their care (Smaje 2023). The imposition of ‘agroecology’ in a top-down, profit-driven fashion from governments and organisations is entirely antithetical to an ecological-, people-driven movement. Unlike fake/junk agroecologies, ‘real’ agroecologies do not see the market as a mechanism to realise true reform and transformation, rather ‘use-value’ is privileged over ‘exchange-value’ as it was for time immemorial before (and still is in many places within) the colonial capitalist epoch.

See our previous blog post for a clear breakdown of the 7 principles of ‘emancipatory agroecology’, and how they can be applied.

AFSA does not claim that all governments and organisations who have (mis)-used the term and principles of agroecology are ill-intentioned. Rather, we are aiming to convey the necessity of understanding the essence of agroecology, as the term grows in use – cautioning against blatant misuse for the benefit of corporations’ bottom-lines. Our aim is for all to possess the ability to critically assess whether or not it is truly transformative, and ultimately working towards realising food-sovereignty.

We must see through the tactics of major corporations and governments, and continue to critically question: who is ultimately benefiting? Where does the power lie? Is this truly transformational?

Join us along the way on the Agroecology Roadshow this October, as we come together to discuss and enact truly transformative agroecology.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn as we share posts about the seven principles of emancipatory agroecologies in the coming weeks!

Further reading:

- Emancipatory agroecologies: social and political principles, Giraldo & Rosset (2022)

- Saying no to a farm free future, Chris Smaje (2023)

- Who Really Feeds the World? The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology, Vandana Shiva (2015)

- Right Story, Wrong Story, Tyson Yunkaporta (2023)